Bare-Knuckle Boxing at the Birth of the Black Country

First published in The Black Country Bugle – 26th April 2021

To try and better understand the development of our region’s name and reputation, in recent months I have been searching for the earliest printed references in the national press to the “black country”, finding the earliest dating back to the 1840s. Fascinatingly, many of them come from coverage of bare-knuckle boxing, alongside stories which open a window onto the importance of spectator sport in fostering local identities and as a working class pastime at the “birth” of the Black Country.

In March 1845 we read of a bout at Sutton Coldfield between Wolverhampton’s Tranter, “a rough looking customer”, and Dudley’s Jenkins, “a wiry looking cove”, where (rather condescendingly!) the writer reports that “the quality of the spectators showed they were principally from the black country”. Modern-day sporting fans will be familiar with the type of “Away Day” atmosphere as, from “an early hour, the roads to the scene of action from the neighbouring towns of Wolverhampton, Bilston, Willenall[sic], Tipton, Wedgbury[sic], Dudley, and other places adjacent, were on continued bustle”.

The crowd was large and boisterous, with “not less than four thousand persons” present, including “at least two hundred of the fair sex, who were not a little vociferous in ‘jollying’ the men to do their best during the action”. With local pride (and bets) at stake it’s no surprise that Tranter and Jenkins were received with “tremendous” and “deafening shouts” from their many “partisans” as they entered the ring.

The reporter begins his account of the fight by describing it as causing “more than ordinary interest among the black diamond fraternity” and we can appreciate the importance to the spectators because we are also told that “both combatants are colliers”. These were true working class heroes, hewn from the same coalface, putting their bodies on the line in front of thousands of their fellow workers here for £25 a-side – six months or more wages for the average pitman.

In the same month we find a second early reference to the region’s name when we hear that “Walsall heroes” George Bibb and Mark Kyte met on Barr Beacon “and fought as gallant a fight as has been witnessed in the black country for many a long year” for £5 a-side.

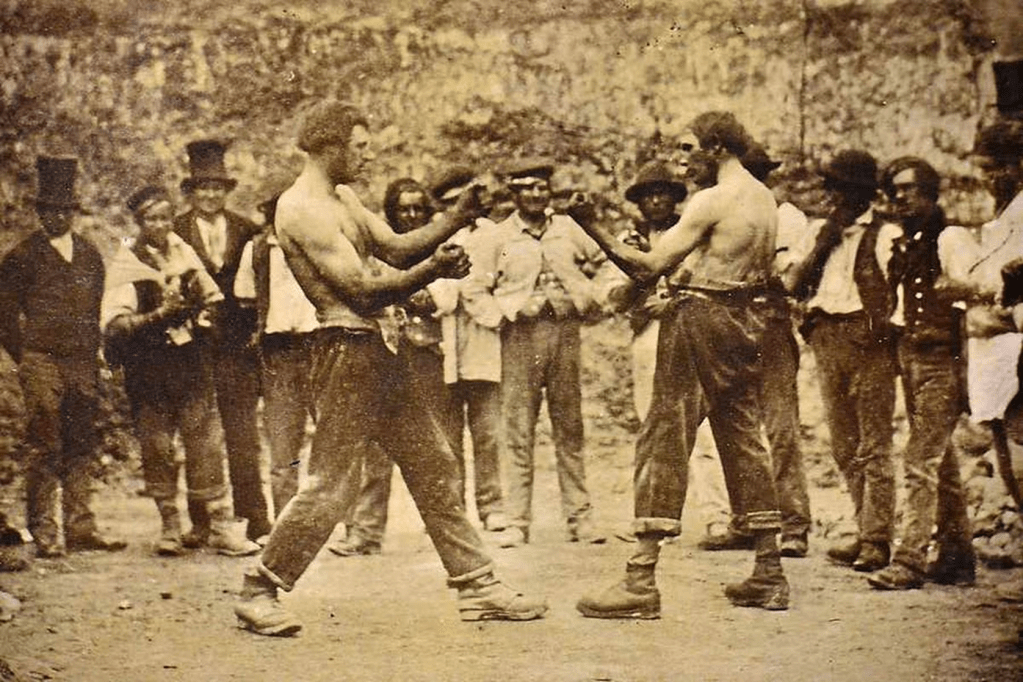

The working and social conditions of the mine and the foundry engendered uncommon toughness and grit throughout the population, but the stamina and determination of these fighters was truly remarkable. The “Prize Ring” regulations for boxing at the time were very different from those of today – fights lasted until one party retired or was knocked out and without gloves this meant long bouts with brutal injury and exhausting punishment.

Grappling and throwing was allowed and each round continued until one or both men were knocked to the ground. Bibb and Kyte’s “manly contested” two hours and ten minutes was a long but not uncommon time to fight for, with Bibb apparently “winning first blood, first knock down blow, and the battle”. A fight attended by fifteen hundred spectators at Delves Green four months earlier lasted a similar length, across 124 rounds.

Although bouts are recorded throughout the area during the nineteenth century, many of the largest in the 1840s were held on the rural edges of the Black Country and Birmingham to avoid the gaze of the authorities who would shut them down and arrest organisers and fighters for breach of the peace. When an open-air location was found which both parties agreed upon, stakes were hammered down and ropes attached to make the ring, but the outdoor nature of the fights could lead to horrendous conditions, particularly in autumn and winter.

An October 1844 fight saw rain in “torrents during the whole of the contest” with “the combatants and spectators being up to their ancles[sic] in mud”. A two hour-long bout in the pouring rain a year earlier ended “to the great discomforture of the ‘Wedgebury Cockers’” when their Darlaston opponent gained victory, even though, “with darkness coming on, we could not exactly ascertain the number of rounds fought”.

Four thousand were present at Castle Vale for the “match between the two heroes of the townships of Walsall and Darlingston[sic]”: George Holden, 24, and 39-year old “veteran” Bob Martin, alias “Whiteheaded Bob”. The Darlaston man seemingly had the larger number of supporters, with “terrific shouts for the old ‘un” in the second round when he “caught Holden under the left ribs, and knocked him off his legs”. By the twelfth, however, the odds were being called 2 to 1 against the “Walsallites”, but with “no takers”, after “Bob appeared at the scratch, bleeding freely”. The fight came to conclusion in the fourteenth when Holden hit Bob (bareknuckled, remember!) with “a jaw-breaker” from which “the brave little fellow fell, as if shot from a cannon”.

We also know from the reports that, like todays sporting stars, the top bareknuckle boxers had their own colours and emblems. For example, West Bromwich’s Tass Parker “sported a flag of blue, with a white spot” before his March 1844 bout with the famous Tipton Slasher, who flew his own pennant – “stone colour, with a pink spot”.

Having beaten all comers in the Black Country, George Holden flew a “chintz shawl-pattern with yellow border for Walsall”, when he was pitched against the traditional Coventry “blue birdseye” of Paddy Gill. Yet again, the “Walsall Lad” was a big draw, with four thousand spectators from “Birmingham, Coventry, Walsall, and towns adjacent . . . wending their way with energy to the scene of action”.

By the start of the twelfth, however, Holden’s nose and ear were both bleeding profusely, “his left ogle nearly closed, the right also tinged, and his left cheek awfully damaged”. The end came in the twenty-first, when after being thrown by Gill, we hear that “poor Holden’s head rebounded from his mother earth like a football” in a sickening blow to Black Country pride.

Like today, local rivalries sometimes went further than simply supporting your hometown hero. After Wolverhampton’s Bill Baker antagonised the miners following victories at the town’s Race Course (now West Park) and Penn in 1830, “the colliers, determined to lower his pride, selected Joe Burton, the Bilstone[sic] Champion, to take the shine out of him”. Three thousand spectators met at Warley and in the early exchanges “deafening” cheers were heard as “Baker was hit off his legs with the force of a sledge hammer” and “hundreds of caps were in the air at one time, and not a few changed owners in their descent”. The Wolves contingent of “lock-lads” apparently “looked all but lock-jaw’d”! Over the hour and a quarter of the fight, however, Baker turned it round, by the end “Burton was hit down, bleeding at all points”, and the pitmen traipsed off despondent yet again.

When the next defeat or relegation comes along, perhaps Black Country sporting fans can take some solace in knowing that the ups and downs of local sporting allegiance have a good two centuries of history behind them. Perhaps they can also remind themselves that it could always be worse – you could’ve just gone 30 rounds with bareknuckle Bill Baker!