Dark Mirrors

Environment, Rivalry and the Invention of ‘Other’ Black Countries

First published in The Blackcountryman, Volume 55, Issue 3 – Spring, 2022

The centrality of our region to the Victorian conception of extractive fossil capitalism is particularly demonstrated in the sheer number of instances where industrialisation in other nations was articulated to readers as the growth of “other” black countries and how use of the region’s name operated as a powerful cypher in discourses around the environment and economic and military competition.

Areas of those nearest neighbours and competitors, France and Belgium, were most frequently represented in comparative terms in the British press but, particularly fascinatingly, by the late nineteenth century the phrase “pays noir” and associated connotations had migrated into the French language, offering us a chance to further re-evaluate the invention of the “original” Black Country through the reflections from this dark mirror.

The Other Black Countries

Nineteenth century comparisons between our region and those in other parts of the world fall into two categories. First, there are those which describe another region as “the Black Country of” that nation, such as London’s Daily News in December 1861 when it discussed economic conditions in the “Belgian Black Country” and the Illustrated Times’ 1865 assertion that the Dessoubre valley “may be called the French Black Country”. They are joined by instances where mention of the region is made comparatively, such as in 1867 when Liberal leader William Gladstone told a crowd that “I read your reply to the Ladies of Wolverhampton on my return from visiting one of the great iron foundries of France, which, though under one proprietorship, is a small ‘black country’ of itself” or The Times of December 1877, which reports from a traveller in Belgium that “the still busy town of Huy, full of mills and foundries . . . recalls our towns in the ‘black country’ of Staffordshire”.

The list of other black countries by no means ends on the opposite shore of the Channel, however. For example, a September 1886 article in The Economist tells us that economic “catastrophes are impending” in “the Silesian ‘black country’” while The Times in December 1874 reports on an area just outside Bilbao that “would be romantic but for the presence of a few matter-of-fact moneymaking Britons, who have turned it into a miniature black country”.

A particularly insightful example comes in the shape of an 1875 book by Hugh James Rose, a chaplain to foreign lead mining companies operating in Andalusia entitled Untrodden Spain, and her Black Country. With his title, Rose was attempting to capitalise on the centrality of the idea of the Black Country to the public discourse around extractive fossil capitalism, hoping that the “must-see” nature of our region for the informed Victorian reader would rub off to make his Spanish equivalent a “must-read”. This tactic was called out by The Times, in their August 1875 review of the work, however, asserting that they could not “approve the title of the book, for it seems to us to be almost deceptive” and that he “quaintly calls [Andalusia] the Black Country of Spain”.

The Times is also the source of three references to the Black Country in relation to Pittsburgh, United States, between 1879 and 1889, including an October 1887 item in the travelogue series “A Visit to the States” entitled “The Black Country of Pennsylvania” and a January 1889 piece describing Pittsburgh as “the Birmingham of the United States . . . the centre of the Pennsylvania Black Country”. Fascinatingly, the “Birmingham of America” moniker used in both of these pieces is recorded regularly in U.S. publications as far back as 1815 and was enthusiastically adopted by the city’s boosters as they desired to establish the city as the key manufacturing provider for the rapidly-expanding Western frontier. While the Times writers pick up on this American usage, it is notable that they additionally chose to also project the idea of the Black Country onto the region to convey a sense of its landscape, society, and industrial activities to a British audience.

Environment

With the environmental impacts of extractive fossil capitalism being so central to the invention of the idea of the Black Country in the Victorian imagination, it is little surprise that we find a long catalogue of examples where some sort of environmental description accompanied the use of the term in relation to overseas regions.

A Dublin University Magazine article in April 1861 about the area around Saint Etienne, France explains that the “coal close at hand has made this cold region a great industrial centre, as coal has given gigantic life to our wonderful Black Country” while going on to explain that it “has gained little or nothing in elegance; it is a smoky, unattractive place, devoted to hard work, and to hard work only”. A Daily News account of a journey through Belgium six months later tells us that “in the night the darkness was broken by the blaze of many roaring furnaces, as in the black country in England”. The Illustrated Times of June 1862, meanwhile, tells us that “any one travelling between Lyons and St. Etienne will be struck by the extraordinary aspect of the valley” whose “entire course bristles with chimneys, lofty furnaces, glasshouse-ovens, and the scaffoldings at pit-shafts, while the atmosphere is similar to that of our own ‘black country’”.

Hugh James Rose’s Andalusian account likewise echoes the descriptions and concerns present in the accounts of many Black Country observers, juxtaposing the “rich tints of the naked sierra and the wild, rugged beauty of the scenery” with the “unsightly . . . rude sheds, the tall, smoking chimneys, the huge piles of broken granite”, where we are told that “save men and machinery there are no signs of life”.

Particularly reminiscent of the earlier “shock landscape” descriptions of the Black Country from writers such as Dickens and Burritt, a November 1879 Times article on Pittsburgh relates how “the dense clouds and streaks of flame filled up the valley in which it stands, [giving] probably the best idea an anticipating American can get of the infernal regions”. The October 1887 travelogue instalment mentioned above takes up a similar theme: “Not long since, this elevated view down into Pittsburg was of a veritable Pandemonium, the terrific character of which can hardly be realized, though it has been not inaptly described . . . as appearing like ‘Hell with the lid off’”.

While these articles describe direct similarities in other regions, others display the deep preoccupation in public discourse that Britain’s industrial advancement had been predicated on an unprecedented despoliation and pollution of the natural environment, the Black Country being a go-to exemplar of this phenomenon. The question of whether the environmental impacts needed to be so grave and whether other nations were able to develop without those consequences was high in the minds of numerous writers.

An 1858 Times review of Oriental and Western Siberia by Thomas Witlam Atkinson tells us that “Iron works of great magnitude are to be found in this region, which Mr. Atkinson likens to the ‘black country’ in Staffordshire”. Before quoting picturesque descriptions of the untouched wilderness of the Issertz valley and the zavod of Syssertskoi, the reviewer asks: “how unlike the country about Wolverhampton is the scenery in the neighbourhood of the Siberian mines?”

Atkinson calls two different places respectively the “Birmingham of the Ural” and “of the Altai” because of their diverse manufacturing industries, with no reference to the landscape around Birmingham or use of the term “black country”. Revealingly, it was the Times reviewer who decided to draw the unfavourable comparison, reflecting the broader preoccupation with our region as a “shock landscape” of extractive fossil capitalism.

A Times article about the German Ruhr in September 1903 tells readers that the region is “almost totally given up to coal and iron” but nevertheless, “cannot be called a ‘black country’, and in no wise resembles the desolation of South Staffordshire, for amid all the pits and furnaces the cheerful Westphalian farms, surrounded by trees and well-cultivated fields, smile properously from the hillside”. In a similar vein, an August 1884 piece in the same newspaper reporting on Alfred Nobel’s oil refining operations in the Russian Caucasus mused upon “[t]he description of his noble refinery, distinguishable many miles away at sea among the throng of rivals by a refreshing absence of smoke, [which] suggests a regret that he could not be induced to start a factory in another Black Country.”

Rivalries

These insecurities, articulated in the use of the Black Country as a comparative catch-all byword for negative connotations of British industrialisation, encompassed much more than landscape and environment, however, also reflecting a more general paranoia about global competition and slipping British economic pre-eminence.

The “cleaner” and more efficient fossil energy afforded to the Russians by Nobel’s oil plants not only seemed to be polluting their surroundings much less, the abundant new fuel offered a competitive edge to the still coal-dominated industrial sector in the UK. The January 1889 Times article on the “Pennsylvania Black Country, . . . famed as a producer of coals and coke”, explained the similar impact of “the recent introduction of the natural gas [which] has been of wonderful advantage to its manufacturing industries in the way of cheapening fuel” as well as reducing atmospheric pollutants, as although “this obscuration is still great, yet I am told it’s nothing like the pall that hung among those Pittsburg hills until a year or two ago”.

The threat to British industry of the rising power across the Atlantic was by no means a new theme, with a fear of relative decline palpable when November 1879’s Times in tells us that “Pittsburg rivalled anything seen in your ‘black country’ in its best days”. We hear that, ominously unlike our region, there were no “dead chimneys . . . [e]very furnace and forge and hammer and roll was working at full capacity, going day and night”. The writer signs off: “Could this sight of wonderfully revived trade be only transported to England, I am confident it would gladden your hearts”.

When a “Special Correspondent” writing in the Birmingham Daily Post in August 1860 reported on the shipyards of Cherbourg, Normandy, we see the region held up as an important benchmark in the measurement of naval superiority. We hear that “the Arsenals of France” were being constructed in “long high-roofed workshops where iron plates are shaped, and oak cut into stout planks [which] rival in extent the largest workshops in the ‘Black Country’ of the midland counties”.

Indeed, most references comparing French locations to “our” black country come peppered with admiring reportage of Gallic ingenuity and industrial progress, such as the Illustrated Times of June 1862 telling readers that an establishment described was “but one of that series of factories which have arisen from the exigencies of engineering operations in France both for scientific and warlike purposes”. Three years later it also reports the “high reputation for those inventions and improvements in machinery which have lately made such progress in France” describing the Arbey brothers’ “immense collection of automatons employed in carvings, drilling planning, turning, and piercing metals, under the direction of a colony of workmen, who will shortly occupy a village that is springing up around the model manufactory”.

While the economic impacts of the U.S. Civil War were adversely affecting British production levels, London’s Daily News’ October 1861 report from Belgium described “new buildings, principally factories, rising up everywhere”, whilst “talk was entirely of cotton and the American war, the natives congratulating themselves on the fact that they had a sufficient stock of cotton on hand to keep them going for two years, and supply all Europe in the meantime”.

Two months later, the Daily News again expressed fears about Belgian competition, this time worrying that essential skilled workers could be lured across the Channel, conjecturing that “it is not likely that artisans will go to the Birmingham workhouse when they can get unusually high wages within a twenty-four hours’ journey from home . . . to the vicinity of the Belgian Black Country.The fiercer the war, and the more the Birmingham makers are crippled, the more urgent will be the demand upon Belgium, and the more will they be willing to pay the workmen”.

Advanced and well-planned new “model” manufactories elsewhere, and the wholesome and productive people they engendered, in stark apparent contrast to the Black Country, were the theme of William Gladstone’s 1867 speech to a crowd in Barrow-in-Furness. Following a visit to the Schneider brothers’ arms plant at Le Creusot, eastern France, he described around this “great French factory”, a “small ‘black country’ of itself, . . . a town of 25,000 inhabitants, wholly built and owned by the miners and ironworkers themselves, who buy their land in fee simple from their employers as they require it for the building”. Gladstone imputed a clear link between the independent means of ownership and self-support offered by employers and his observations of the moral standards of the town, claiming that, “during a ten days’ stay, I did not see a drunken man, though I once heard one” and neither did he see a policeman or soldier.

Les Pays Noirs

While these “other” black countries served as useful mirrors for the literate classes in Victorian Britain to understand the spread of extractive fossil capitalism and measure and project their own preoccupations about its environmental and social consequences, as well as global economic competition, the idea of the Black Country itself was migrating to febrile new shores.

A search through the Belgian and French national libraries’ newspaper and periodical databases shows the term “pays noir” beginning to crop up in francophone discourse from the 1850s, with increasing regularity in the 1860s and 1870s. Almost all of the references during these decades occur in reports or travelogues about the “original” Black Country in England. Keeping abreast of political and economic developments in Britain was clearly of an equal interest to French and Belgian readers and writers as vice versa and we can detect the direct migration of the idea of a “pays noir” into French from English by its frequent prefixing or suffixing during this period with “as the English call it”, or words to similar effect.

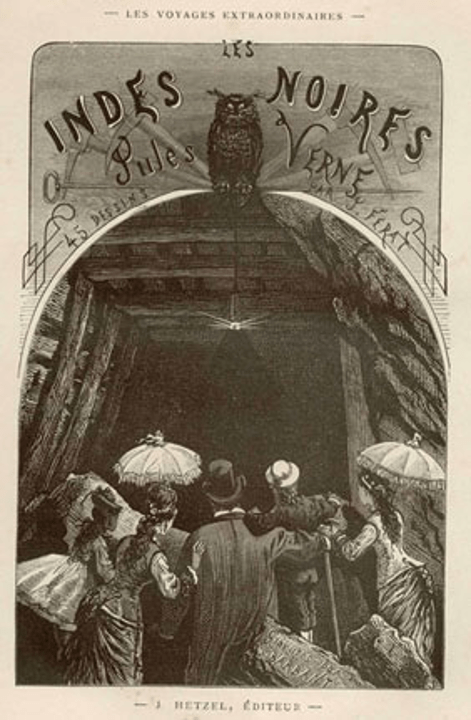

Two examples show early French language uses of the term as a catch-all for an industrial region, although these are the exception to the general pattern. A February 1852 review in La Presse described the play Les Blooméristes as evoking “a black country of factory smoke, [where one might] sniff the railway boilers across the country”, while a lecture on geology from Paris’s École Centrale d’Architecture in 1866 introduced students to the concept of “the land of coal, the black country as the English call it. Our neighbours talk also of the black Indies, by allusion to the riches they withdraw from the combustible fossil”, before going on to list the key extractive fossil regions in France and Belgium, as well as Britain, where we are told of the commonality between them because of the industry “which has given to all these populations of miners distinctive habits and characters”.

The use of the term independently of the “original” Black Country, however, really gained traction in francophone publications in the late 1870s, and particularly the 1880s. In January 1876, the Parisian newspaper La France entitled a travel account of Saint Etienne’s industrial region as a “Voyage au Pays Noir” and in June of the same year the Belgian L’Écho Du Parlement was one of a number of publications to reprint a report of a new Liberal association in Jette Saint Pierre, north of Brussels, as being “established in the middle of the black country”.

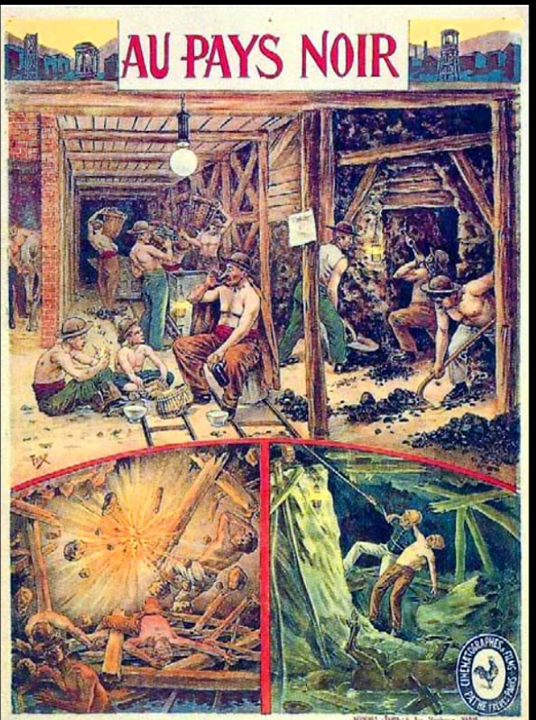

The 1850s and 1860s were the peak years of Belgian industrial expansion, spurred on by post-independence investments in railways and deliberate programmes to import foreign, particularly British, technology and expertise. The following two decades, however, saw consistent economic depression and prolonged and deep hardship for mining and metallurgical workers. During the 1880s the term “Pays Noir” became definitively attached to the region surrounding Charleroi, which remains known as such to this day.

It was at this point that the environmental and social connotations associated in British discourse with the idea of “black countries” also firmly established themselves across the Channel. In March 1878, the Belgian newspaper Le Bien Public, describing a trend towards civil rather than religious burials among young women in the industrial town of Houdeng-Gœgnies explains that it was “a black country, alas! Physically and mentally”, while Le Courrier De L’Éscaut, discussing Catholic associations organising to oppose freemasonry among the political and industrialist class in Hainault in April 1879, declared that: “It is a black country that must be enlighted”.

Paralleling this negative imaginary usage of the term was a coterie of popular and widely reported and exhibited artists and writers who made the region their base and inspiration, most prominently Constantin Meunier, a working-class painter and sculptor who challenged the high art world by forefronting representations of working people and the ravaged industrial landscape.

Lasting Reflections

In our contemporary mission to re-forge anew a regional identity, the invention of the Belgian Black Country and the continuing French language usage of the term into the twenty-first century unleash a number of tantalising opportunities. That the idea became firmly implanted at a moment of acute industrial crisis in the 1870s and 1880s serves to reinforce our appreciation of how closely the invention of the idea of the Black Country in England, at a time of considerable upheaval in the 1830s and 1840s, was driven by the similar preoccupations of bourgeois, literate public discourse with similar concerns about environment, social fabric, and political instability.

In Belgium, France, Pennsylvania, and beyond, the dark mirrors of our sister regions not only serve as reflections from which we can impute the myriad items of negative imaginary baggage piled upon our region’s reputation over two centuries, they also offer scope to compare our shared histories and industrial heritages, not to mention learn from each other about our respective work of regeneration, be that the regeneration of our economies, our environments, or our identities.