Environment & the Invention of the Black Country

The “Shock Landscape” of Extractive Fossil Capitalism

First published in The Blackcountryman, Volume 55, Issue 1 – Autumn, 2021

Dud Dudley, the Newcomen Engine, Abraham Darby – the importance of the inventions and inventiveness of the Black Country to the creation of the Industrial Revolution is proudly celebrated in our region, as is the labour which made the products and tools which helped build the modern world. But there is one, less investigated, invention of the Industrial Revolution that has particularly interested me in recent months – the idea of the Black Country itself.

As we reforge anew in the twenty-first century an identity rooted in our industrial heritage, more than ever it seems vital to understand as best we can what “the Black Country” meant when the name and the concept were first associated with the region in the wider public consciousness and to trace the evolution of this idea, particularly the ways in which it was projected onto the area from the outside. In order to do this, I have searched for and catalogued every mention of the term “black country” in the British Library’s nineteenth century national and regional newspapers and other digitised publications.

While the first utterances and any local, popular adoption of the region’s name are lost in the mists of myth and folk memory, the term is first recorded in print in the early 1840s. The 1830s and 1840s were a critical juncture in the transformative reorganisation of society produced by industrialisation and attitudes and concepts of environment, labour, and poverty. The New Poor Law of 1834 was followed by the end of British slavery in 1838, while the 1840s proved a tumultuous decade of Chartist political action, large-scale industrial strikes, and devastating famine in Ireland. Tracing the layers of meaning applied to the term “Black Country” by the literate, middle and upper class Victorians, there seems little coincidence that it emerges at precisely the moment that the transformations of social, economic, and environmental life were high in the public imagination.

While they admired the unprecedented wealth and prosperity generated by the industrial capitalist system, the ingenuity of new technologies, the harnessing of motive power, the improvements in communications, transport, architecture and human comfort they created, and the political and military predominance they afforded Britain, it was inescapable to notice that industrialisation was also wreaking dire environmental consequences.

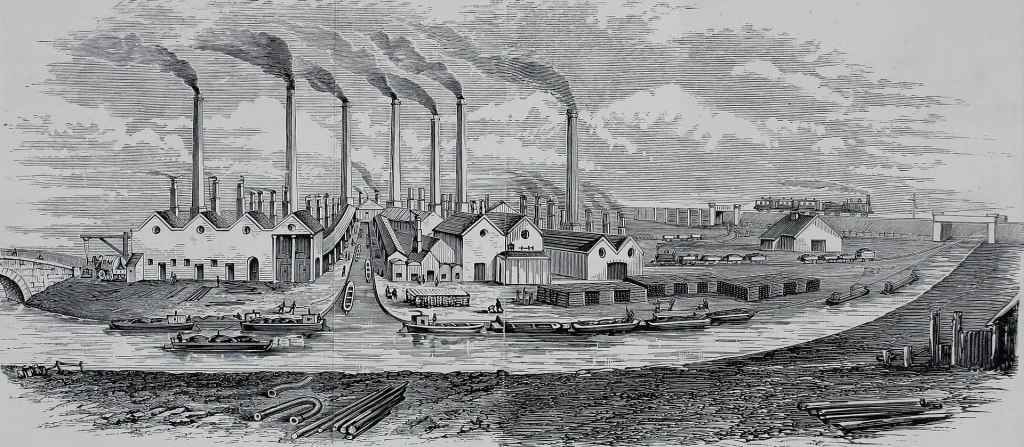

A detailed survey of all printed references to the name up until the 1860s indicates that the Black Country was understood as the “shock region” and “shock landscape” of extractive fossil capitalism. They, and the world, had literally never seen anything like it before. As the name entered the British public imaginary, it caught on very much because it offered great utility in expressing in one term all of the environmental connotations of its “blackness”: the black, polluted sky, the coal which lay underneath the whole region and provided much of its wealth, and the colour of the sooty, grimy, and coal-dusted ground, buildings, and people.

Environment and the Invention of the Black Country

As people sought to construct a psychological framework in which to understand these transformations, the Black Country, as the first region anywhere in the world wholly expropriated and rearranged into the service of coal and iron, became the key reference point when Victorians wanted to point to the environmental devastation which modern industrial society was contingent upon. In the literate and popular imagination of nineteenth century Britain, the Black Country was the archetype, the original, the standard that other extractive and metalworking regions, across the UK and the world, were compared to.

Key to the creation of the idea of the Black Country as the “shock region” and archetype of fossil capitalism was the impact of Dicken’s blockbuster The Old Curiosity Shop. Serialised monthly in 1840-41, the unfolding drama of Little Nell and her grandfather’s flight from debt and exploitation drove circulation to an astonishing 100,000 monthly copies and Harry Potter-levels of reader fanaticism – a riot ensued in New York harbour as devotees fought to be the first to get their hands on the final volume of the publication when they arrived in America.

Throughout the book, which so captured popular imagination and conversation in its initial run and hugely successful novelised editions, Dickens uses landscapes and locations as allegorical diorama for the unfolding drama. It was the Black Country which Dickens chose for the dramatic peak of his narrative, as the morbid backdrop where (spoiler alert!) Nell becomes sick through pollution, exposure, and hunger with the illness that eventually takes her life.

Having passed between Birmingham and Wolverhampton in 1838, like most visitors, Dickens very much reacted with shock at “such a mass of dirt, gloom, and misery as I never before witnessed”. For Dickens, the landscape of the Black Country offered the perfect symbolism for his literary exposition of the most pernicious environmental and social impacts of the emerging industrial modernity. Indeed, German theorist Theodor Adorno described Dicken’s “first images of Wolverhampton” as the “embodiment of hell in the bourgeois universe”.

The literate audience of the 1840s were introduced to this emotive idea of the region through Dicken’s powerful description of an environment,

“where coal-dust and factory smoke darkened the shrinking leaves, and coarse rank flowers, and where the struggling vegetation sickened and sank under the hot breath of kiln and furnace, making them by its presence seem yet more blighting and unwholesome than in the town itself . . . they came, by slow degrees, upon a cheerless region, where not a blade of grass was seen to grow, where not a bud put forth its promise in the spring, where nothing green could live but on the surface of the stagnant pools, which here and there lay idly sweltering by the black roadside. Advancing more and more into the shadow of this mournful place, its dark depressing influence stole upon their spirits, and filled them with a dismal gloom. On every side, and as far as the eye could see into the weary distance, tall chimneys, crowding on each other, and presenting that endless repetition of the same dull, ugly form, which is the horror of oppressive dreams, poured out their plague of smoke, obscured the light, and made foul the melancholy air”

The first recorded use of the region’s name comes from a Staffordshire Advertiser article of 1841, with a handful of others from London and regional newspapers before William Gresley’s Colton Green: A Tale of the Black Country, or a Region of Mines and Forges in Staffordshire was published and decisively associated the name with the region 1846. Although Dickens does not mention the term “black country”, he undoubtedly established the imaginative ferment from which Gresley’s and future descriptions and conceptualising of the region take a lead. Indeed, his environmental description bears remarkable similarity to Dickens’s:

“you see all around a confused mass of chimneys vomiting forth volumes of black smoke, blazing furnaces, glowing coke hills, heaps of ashes round the pit mouth, steam engines plying their incessant work, and other signs of human drudgery. The whole country is blackened with smoke by day, and glowing with fires by night. Overspread with the refuse of coal and coke”

As the idea of the Black Country became firmly implanted into the popular consciousness into the 1850s, with increasing volume of references to the region’s name, its status as a “shock region” that literate people were expected to know about, have an opinion upon, and to have witnessed themselves was predicated greatly upon increasing access to that other great invention of the coal age: the steam train. An 1851 “Rides on Railways” guidebook advised tourists on the way to the Lakes, Peaks, and Snowdonia to pay equal attention to the “black and unwholesome” “perpetual twilight” and “dark landscape” of the Black Country as an essential counterpoint to the natural, untouched beauty of their final destinations.

A much reprinted 1852 Times account of the journey of the region’s most famous train-based observer, Queen Victoria, tells readers of the “striking contrast to all that preceded it” of this “Pandemonium” ; “Nature has not been kind to the surface of the ‘Black Country,’ but for external beauty has supplied mineral wealth”. An August 1854 piece in London’s Morning Post stressed the must-see credentials of the region’s landscape for discerning tourists, recommending a walk of “Twenty miles through the grim black country round Wolverhampton, with its red furnaces glaring out from the darkness like angry eyes”, as being as worthy of visit as the Lake District, Picardy, and the Kentish hop fields.

Another Black Country train ride provided the backdrop for a much reprinted 1857 lecture from Baptist preacher Arthur Mursell, first published in the Manchester Times, where we hear that,

“black enough it is. If you go through it by day, your eye wanders over a vast expense of grimy country, unrelieved by the blushing of the uprising flower, and scarcely by the gleaming of a single blade of grass. Vast mounds there are indeed, but not of fruit or verdure. They are swollen, dusty heaps of coal, and the offal of molten iron, and the whole prospect looks like a huge graveyard”

As Mursell elaborates the moral and social “blackness” that apparently accompanied the environmental devastation, the imaginative power that had been imbued into the idea of the Black Country is demonstrated through its use as the archetype for the negative impacts of industrialisation in the very “shock city” of the factory system, Manchester.

The idea of the Black Country as shorthand for all of the negative, particularly environmental, impacts of extractive fossil capitalism repeatedly comes to the fore in the regional and national press, such as the fears of the York Herald in 1854 that Middlesbrough was turning into a “second Staffordshire” and Stokesley into a “second Wolverhampton”, where the “Elysium” that was the “garden of Yorkshire” would be subjected to the “devastating effects” of industrialisation and mining. For a November 1857 writer in the Liverpool Daily Post, meanwhile, extolling the health benefits of rambling holidays in remote natural locations, the go-to example of a polluted area one might escape from was obvious, as they pondered how, “the rector of an English parish, emerges from the smoke of the ‘black country’ to spend a fortnight in August among the Highland hills”.

Indeed, the idea of the Black Country as the fundamental exemplar of an industrial landscape led to its use as an adjective in two summer 1859 instances. The Birmingham Daily Post described “‘black country’ symptoms” as one approached Ironbridge on a(nother) train journey and the Worcestershire Chronicle described “two steep ‘black country’ looking escarpments” on a new railway line.

By the end of the 1850s and start of the 1860s, the region’s name had become the benchmark against which pollution and environmental damage was measured against. In 1859, the Leicester Journal described post-harvest fires clearing farmland as looking “like the black country”, while both the Standard and Illustrated Times in London reported the Earl of Derby’s 1862 complaint that pollution near his St. Helen’s home had produced “an air of desolation” where “vegetable life did not thrive” unknown outside of the Black Country. The only comparison a letter to The Times in 1863 could make of buildings “blackened to blackness” in Jarrow was to the “grimy districts of the Black Country itself”.

Not only was the region a benchmark to be compared to, it was an exemplar to be compared snobbishly and condescendingly against. In 1862 the Leamington Spa Courier complained that a proposed bridge in blue brick “may suit the ‘black country’, but they will hardly harmonize with the appearance of the buildings in our fashionable town” and the Northampton Mercury reported a town council speech congratulating the well-to-do residents “upon living in the midst of a most beautiful country” unlike those “many who made their fortunes in the black country”.The Times, in January 1864, meanwhile, responding to a Devon MP’s complaint of a lack of industrial investment in his constituency, observed that “its less fortunate neighbours under ‘the smoke’” would “rather live there than in ‘the black country’”.

The Must-See “Shock Region” of Extractive Fossil Capitalism

The early 1860s witnessed a particular spate of published travel accounts in magazines and newspapers stressing, as their predecessors had done, the must-see nature of the region with accounts that often combine Dickensian descriptions of the landscape and environmental devastation with some admiration for the awesome spectacle and power on display.

The well-publicised and much-excerpted travelogue, All Around the Wrekin, by Walter White, released in 1860, makes much of contrasting the idyllic greenery and picturesque Shropshire countryside with the industrial “shock landscape”. We are told that the region’s name is “eminently descriptive, for blackness everywhere prevails; the ground is black, the atmosphere is black, and the underground is honey-combed by mining galleries stretching in utter blackness for many a league”, while stressing to readers that the experience of observing the region’s landscape “is marvellous, and to one who beholds it for the first time by night, terrific” describing in detail the forges, mines, factories, and smoke and explaining how the “effect is one that vividly excites the imagination, and is not easily forgotten”.

1861 travelogues in Dublin University Magazine and Popular Science Review, respectively, described the region as “a sight worth seeing” and asserted that “Nothing in England is more impressive – we may say, more sublime – than the “Black Country of South Staffordshire, as you are carried through it by the railway at night”. In the same year, London magazine Temple Bar reported that “We may admire now the advance of commercial enterprise in it all; but one cannot help a feeling of regret at losing our favourite walk, and knowing that the violets and primroses we used to admire on the hedgerow side are deeply buried in dust and ashes”, a sentiment echoed in an 1863 article in the Edinburgh Review which outlines the environmental damage of industry in “those portions of the Midland district from which verdure has retreated before the encroachments of the manufacturer”.

This preoccupation with the destroyed environment and vital importance to national prosperity was addressed by the Times in December 1866 as Queen Victoria made Wolverhampton the site of her first post-mourning public appearance, when we are told that “It is certainly not inviting, this Black Country, to the everyday tourist . . . however unattractive to the eye, [it] possesses the greatest interest to Englishmen as one of the busiest and most important among our seats of industry”.

Bearing in mind the growing popularity and affordability of railway excursions, and the many exhortations of writers encouraging tourists to pay attention as they passed through the region, by the time U.S. Consul Elihu Burritt came to publish his Walks in the Black Country and its Green Border-Land in 1866, he was probably justified in declaring that, “[d]oubtless a majority of our English readers have passed through this remarkable district once in their lives, and remember its most striking features”. Of course, the “readers” he addressed were specifically the literate, educated, chattering classes, people he expected to have an opinion on, but likely not be people of, the Black Country.

Writing during, or shortly after, the end of his homeland’s devastating Civil War, Burritt, a pacifist and peace campaigner describes the landscape as viewed from Dudley Castle as a vast battle where,

“Nature . . . has the underhand, and from the crown of her head to the sole of her foot she is scourged with cat-o’-nine-tails of red-hot wire, and marred and scarred and fretted, and smoked half to death day and night, year and year, even on Sundays. Almost every square inch of her form is reddened, blackened, and distorted by the terrible tractoration of a hot blister. But all this cutaneous eruption is nothing compared with the internal violence and agonies she has to endure. Never was animal being subjected to such merciless and ceaseless vivisection. The very sky and clouds above are moved to sympathy with her sufferings and shed black tears in token of their emotion”

Some 25 years on from Dickens, Burritt’s work represents the culmination of the process establishing the idea of the Black Country in the Victorian consciousness as the archetypal extractive fossil capitalist region and benchmark against which environmental damage wrought by industrialisation elsewhere was measured. Although channelling the preoccupation of previous writers and commentators with the terrific sights, sounds, and pollution of industrialization, like Walter White, he also reports his observations of workshops and manufactories in action, the labourers and processes he saw, and outlines the global reach of the region’s exports.

It was this combination of the ingenuity and productive capacity of the Black Country with its devastated and shocking landscape, so well-articulated by Burritt, which made the idea of the region such a compelling concept to the Victorian mindset. The modern world created by industrialisation was generating unprecedented communicative and technological improvements, profits, wealth, and global political and military hegemony. It was also creating environmental consequences of a type and scale never before seen, none more awesome than the landscape of the Black Country.

An assessment of the invention and development of the idea of the Black Country shows us that when the Victorian upper and middle classes saw the first “shock landscape” laid waste by extractive fossil capitalism, their revulsion and condescension was not just a direct reaction to what they saw. It was compounded by the deep-seated preoccupation that their progress and prosperity was built upon this natural catastrophe.

This essential link between the industrial and environmental in the generation of the idea of the Black Country provided the foundation upon which ideas about morality, labour, poverty, social problems, gender, race, and colonisation were layered on to the reputation of the region and its people during the nineteenth century, complexities which continue to resonate today and which I hope to unpack further in coming months and years.