Representing Everyone?

What Can We Learn From the Black Country’s Divisive Flag-Making Experience?

First published in Flagmaster, Issue 164 – Summer, 2022

In the space of a few years the Black Country’s flag has been enthusiastically adopted, becoming the most-purchased regional flag in the UK. Sadly, the flag has also become the centre of an ongoing and toxic “culture war” over its divisive chain symbology, in a region deeply involved in providing the metal goods that underpinned enslavement.

By analysing the flag-making process, can we learn lessons which refine a best practice for flag-making that aims to invest in a truly broad and growing base of participation in local heritage?

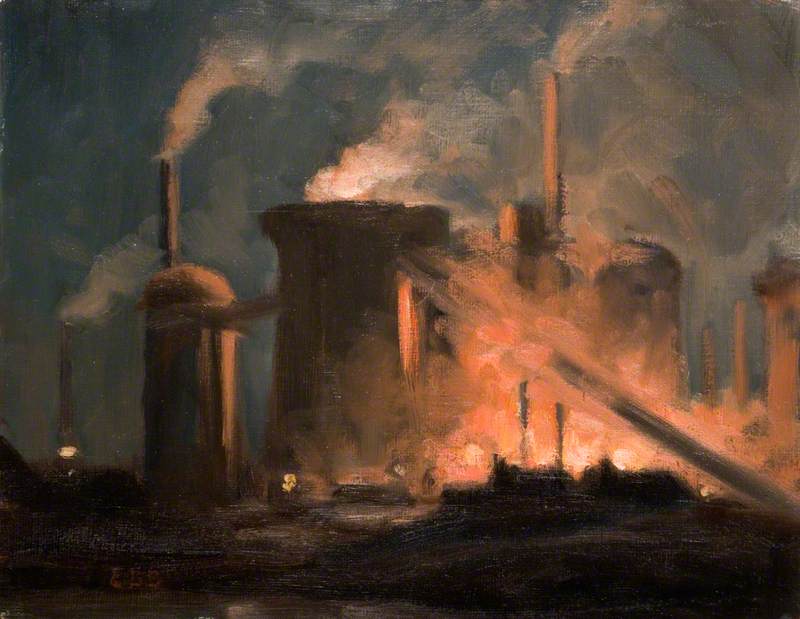

“Black by day and red by night, it cannot be matched for vast and varied production, by any other place of equal radius on the surface of the earth”

Crystallising an image and idea developed over decades, the 1868 words of the American consul to Birmingham, Elihu Burritt, epitomised the truly global significance of the Black Country and its unique, troubling appearance, cementing the region’s name and reputation in the popular consciousness.

The site of existing metalworking industries and workshops and pioneering experimentations of smelting with coke prior to the 18th century, the proximity of coal seams made the area ideal for iron production. It was a multi-focal region, with numerous towns that expanded rapidly in population, particularly in the 19th century, with migrants attracted to the burgeoning industries servicing increasing global demand.

Due to the combination of a unique concentration of mineral deposits and as the site of early technological breakthroughs at the birth of the industrial boom, the region was the first “shock landscape” on the face of the planet to be wholly expropriated to extractive fossil capitalism.

The name and idea of “the Black Country” became definitively linked to the extractive and metallurgical region to the north and west of Birmingham at the pivotal moment of establishment of industrial Britain’s newly-forged economic and social settlement in the ferment following the Reform Act of 1832, the New Poor Law of 1834, the end of British slavery in 1838, and the crunch point of growing Chartist and trade union mass political activity.

Shortly after the region offered the backdrop of the poisonous hellscape at the nadir of Dicken’s first blockbuster, The Old Curiosity Shop, the name first appeared in print in the early 1840s, gaining increasing traction in the minds of literate outsiders to the region as Victorian commentators wrote of the “must-see” nature of the region for tourists and travellers on the newly-established railways.

And layer upon layer of condescension continued to build well into the twentieth century and beyond. Commentators continued to remark upon the ugliness of the industrial and post-industrial landscape of the Black Country and often continue to ridicule our distinctive regional dialect. Lonely Planet in 2009 decided to grab some headlines by unkindly naming Wolverhampton as the 5th worst city in the world to visit, while a 2015 ONS survey named it as the least prosperous and satisfied place in Britain.

Nevertheless, a strong working-class culture, identity, and deep pride developed and persists in the area, although ties until at least the 1960s were far stronger to towns and local communities, as well as historic county allegiances, than to any overarching regional “Black Country” identity. The old joke goes that the Black Country “proper” always began at the next town, rather than yours!

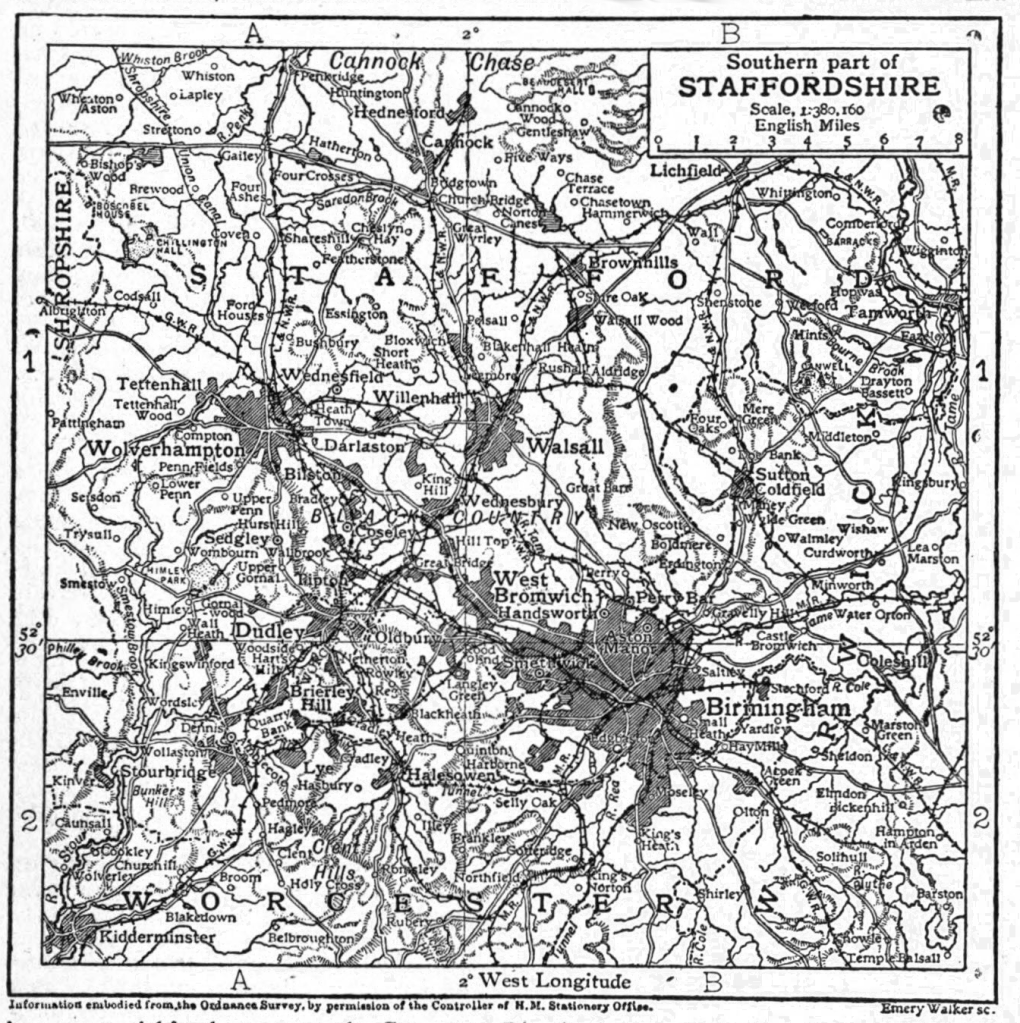

Indeed, if there’s one way guaranteed to start a fight in a Black Country pub it would be to ask the question of what does or doesn’t constitute the region. For many it encompasses only those areas where the 30-foot coal seam comes close to the ground, for others it is the wider former industrial region, mainly within Staffordshire, but including parts of Worcestershire, stretching all the way from Wolverhampton in the west to the edge of Smethwick in the east, Walsall and Wednesfield in the north and Stourbridge and Halesowen in the south. More recently, in political and official geographic terms it has come to refer to all of the four present-day boroughs of Wolverhampton, Walsall, Sandwell, and Dudley, although some areas in surrounding South Staffordshire, Cannock, and Worcestershire assert claims as well.

Concerted efforts to preserve and celebrate the region’s industrial and cultural heritage began in the 1960s as dialect dictionaries were created and popular folk tales, poetry, and humour were collected and written, and the Black Country Society was founded, providing a thriving platform for local historians, archaeologists, and writers, just at the moment that many traditional industries and ways of life began to wane.

The regional heritage hub, the Black Country Living Museum, was founded in 1975 to bring the objects, buildings, and working machinery salvaged from the wrecking ball and the scrap man into the care of conservators and allow the public to explore, learn about, and commemorate the region’s industrial past. It now boasts preserved terraced streets, shops, pubs, working industrial workshops, and canal tunnels, preserving both physical and cultural aspects of the region’s history. This flourishing of attention and interest in regional heritage and identity coincided with the managed industrial decline of the 1970s and 80s which had a drastic and hugely damaging impact on the local economy.

Our present-day reinvigoration and reinvention of regional identity is built upon the deep foundational work of these institutions and the writers and researchers who invested huge resources and expertise in capturing and communicating our industrial heritage at that post-industrial tipping point. Institutions and community groups around the region have worked successfully in recent years to combat this negative stereotyping, reinvent the area’s reputation, and raise its national and international profile to encourage new investment and capitalise on a growing demand for industrial heritage tourism.

Campaigners have worked to literally get the region on the map, with the Ordnance Survey finally adding the name in 2009. The annual Black Country Festival is now held on Black Country Day, the 14th July, marking the inception of the world’s first successfully steam generator, the Newcomen Engine, at Coneygree Coal Works in Tipton in 1712. The Black Country’s historically-significant landscape has now also achieved UNESCO Geopark status thanks to the work of local campaigners.

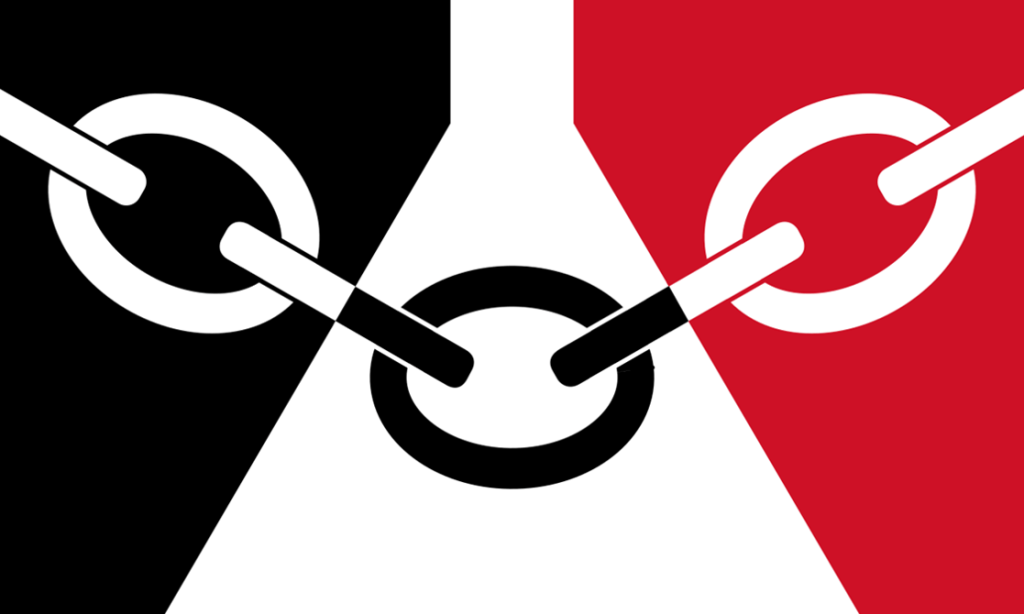

Building upon these decades of activism and organising and inspired by 2012’s Diamond Jubilee flag design programme, the Black Country Living Museum launched a competition to design a flag for the region. Submissions were invited and initial entries were narrowed down by a judging panel to six finalists. This selection was then put forward to public vote, with the winner being that submitted by 12-year-old schoolgirl Gracie Sheppard.

And the design is very striking in its simplicity, geometry, and colour palette. It draws direct inspiration from Elihu Burritt’s seminal description of the industrial sky – “black by day, red by night” – flanking a depiction of the distinctive glassmaking chimneys of Sheppard’s native Stourbridge. A series of linked chains complete the field, representing the key metalworking industries.

The popular response and adoption of the motif has been hugely impressive. The flag’s design and subsequent launch tapped into the deep pride in regional industrial heritage and a growing desire for greater recognition, providing for a flourishing, reinvented, and reinvigorated Black Country identity. It quickly became the biggest-selling regional flag in the UK, and you can see it all over: adorning people’s homes, on car stickers and t-shirts, particularly prominent outside pubs and clubs and local businesses of all kind, at music festivals, football matches and other sporting occasions, and prominently on social media profiles and groups.

In this small selection of images we can see a lemur sporting the flag at Dudley Zoo, the wrestler Trent Severn sporting his Black Country pants, and a Walsall F.C kit.

The speed and scale of the flag’s adoption very much seemed to outstrip even the most optimistic predictions of the competition’s organisers and to initial appearances, crystallise a positive and uniting branding in a way previous campaigns could never have hoped. Seemingly this was radical and positive vexillology in action and a chance for the competition organisers to put their feet up and watch the motif’s steady and meteoric progress! . . .

Well, not quite . . .

Representing Everyone?

Fast forward to 2015, and historian and activist Patrick Vernon, MBE, a native of the region, wrote an article for The Voice newspaper ahead of Black Country Day expressing his discomfort with the chains which take a prominent place in the flag. He argued strongly that the use of this imagery indicated a total lack of awareness of the region’s links to slavery and the alienating and upsetting impact of its inclusion, particularly for those of Caribbean and African ancestry.

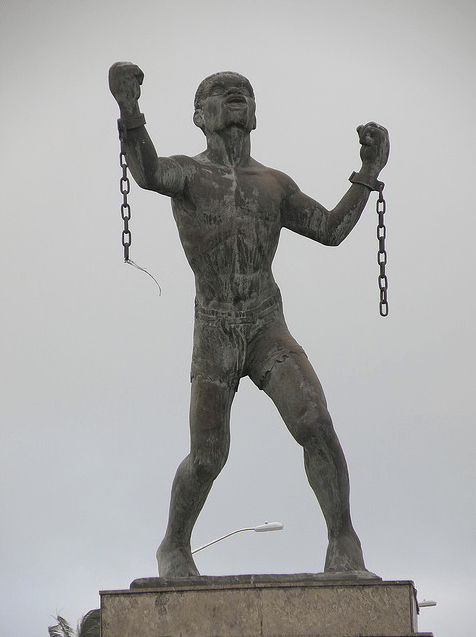

He explained with clear historical credence: “That is why I find the Black Country Day logo offensive, as the foundries and factories made chains, fetters, collars, padlocks and manacles which were used on slave ships from Africa and in the plantations during slavery in the Caribbean and North America. The iron was used for trading by merchants for exchange in Africa. Such was the extent of this trade, Henry Waldram, a Wolverhampton ironmaker, advertised his specialism in Sketchley’s and Adam’s Universal Directory of 1770 as ‘Negro Collar & Handcuff maker’.”

This theme was picked up again in summer 2017, when Eleanor Smith, newly elected MP for Wolverhampton South West, and the first Black Country MP from a Black background, also publicly raised the problematic nature of the flag’s design. In an interview Smith explained: “I have serious concerns about the racist connotations of the flag, particularly the fact that chains are being used to represent the Black Country. The white on black imagery used together with the chains . . . when you break it down I’m not going to pretend it doesn’t worry me as a black person. People have to understand that it can be seen as offensive. . . . It is not something I feel comfortable about standing in front of . . . I understand the flag was designed by a young person, and I don’t for one minute think they realised its connotations. I think it is time for an intelligent conversation about the flag. I would look to have it changed.”

While Vernon and Smith have generated the most attention for the issue, their interventions as prominent Black figures from the region have voiced the views of large numbers of people from the Black Country from all backgrounds who have previously lacked either the platform or courage to make public statements on this subject.

As with most areas of the UK, scholarship and general awareness about the region’s deep linkages to colonisation and enslavement has been lacking in focus, funding, capacity, and visibility. This, often wilful, amnesia is but one, regional, manifestation of what Paul Gilroy describes as our wider “postcolonial melancholia” and failure to face up to and come to terms with our imperial history and the legacies of Empire.

The public interventions by Vernon and Smith offered a great “teachable moment”. Here was a golden opportunity to have an open, honest, awkward, painful but wholly necessary discussion about the Black Country chains, manacles, and torture implements that supplied the transatlantic slave trade and plantation economies. A chance to highlight the role of Black Country suppliers to the gun trade and metal goods which supplied Liverpool and Bristol slave traders, the nails that literally held together the British Empire, or the vast colonial markets for regional manufacturers that sustained tens of thousands of jobs in various trades throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and beyond.

The local media and politicians from all sides of the spectrum, however, did not see the opportunity in this way. The biggest selling regional newspaper, the Express and Star, were quick to pick up on the gift the issue offered in terms of viral coverage to set up a highly polarising public discourse which no doubt provided them with huge amounts of clicks, shares, comments, additional readers, and advertising income. Capitalising upon the insecurities and resentments that two centuries of condescension, disempowerment, and recent post-industrial abandonment have generated, most press coverage framed Vernon and Smith’s comments as a direct attack on reinvigorated local pride and identity, helping fuel a massive Twitter and social media furore which built an overwhelmingly strong and vociferous reaction against the comments on both occasions.

There was yet another reprise of the controversy picked up by the local and national press in summer 2020. In the wake of Edward Colston’s toppling, the local Fire Service temporarily stopped flying the flag from their stations while they reviewed its design and connotations, following concerns raised by some staff members, which saw the flags reinstated after a few days.

As local ire was whipped up, within the thousands upon thousands of votes in online polls, posts, shares, and comments were a small but sizeable minority of downright trolling, insulting, or abusive posts. One Wolverhampton man was eventually prosecuted for racist and threatening messages sent to Smith.

It was as if an entire new regional mini-industry grew up overnight on both occasions to target and shut down two prominent Black voices who dared to voice their well-evidenced arguments and deeply-considered and rational personal feelings and opinions (and those of thousands of others across the region) as “barmy”, “ridiculous”, and “nonsense”. To compound this offence and insensitivity, an eminent Black historian and the first Black secretary of the UK’s largest trade union were groundlessly accused by a host of clearly historically-illiterate politicians and commentators as not understanding the region’s working-class history.

How Did We Get Here?

For vexillologists, not to mention everyone working to celebrate and cultivate local and regional heritage and identity, there are perhaps two pertinent lessons to take from the unfortunate series of events that have occurred in the Black Country:

First:

An analysis of the way in which the flag-selection process was conducted should inform the organisers of future flag competitions across the UK to ensure these are truly representative projects.

Second:

We need to situate flag-selection and promotion within the broader ecosystem of local heritage and history to appreciate that creating these symbols is not, in isolation, an adequate practice of commemoration, celebration, and representation. Designing and championing a new flag needs to build on a broad, deep and existing foundation of organising and requires long term legacy planning and resource to ensure it continues to resonate with its community.

In the Black Country, lobbying for a flag for the region began in 2008 when Philip Tibbetts, now the Flag Institute’s Community Vexillologist, proposed and launched an initial design as a way of sparking a conversation in the region, gaining media attention for the flag proposal and seeding the idea in the minds of institutions. This priming came to fruition in 2012 when the Black Country Living Museum launched their call for designs and ensuing public competition.

1,500 votes were cast, both online and in-person, and the current design was proclaimed the winner and began to be flown and promoted in August 2012. On the surface that seems like quite an appropriate way for a museum to go about designing a new logo or motif to support their work and the Black Country Day celebrations.

This process raises an important question for flag competitions and adoption more generally, however:

Who actually has the right to assert that their competition and their flag is a true representation of the identity and will of their whole community?

Seemingly, a single institution in a huge region perhaps overreached themselves somewhat in this regard.

The subsequent huge success of the flag undoubtedly took the museum by surprise and was probably beyond their wildest dreams. After a disappointing level of activity and recognition of Black Country Day in 2013, renewed efforts were made to reboot the festival, which included Dudley Council deciding to start flying the flag on public buildings, an important part of their strategy to develop the local heritage tourism economy and part of their (unilateral and not uncontroversial) rebranding of Dudley as the “historic capital of the Black Country”.

While the other three local authorities have to some extent recognised the flag and encouraged Black Country Day celebrations, the way its “official” adoption has grown on an ad hoc basis means there was never a concerted plan and thought of how to gain universal consent. 1,500 votes sounds like a decent amount of votes for a museum’s new logo competition, but as part of an open public discourse on choosing a flag to represent the identity of a region of over 1.1 million people, it was actually less than 0.14% of the regional population.

While there was a publicity campaign and some coverage in the local press, it’s fair to say that the vast majority of people in the region had no idea the competition was happening. The actual electorate for the flag therefore really selected itself based on factors such as an existing interest in “traditional” local heritage, visiting the museum during the voting period, reading or watching a news story and being interested enough to find out more or vote, or hearing through word of mouth or other indirect means that the competition was going on.

Thinking about the vast diversity of locations, class, gender, age, language, ethnicity, and race across the Black Country, without any statistical evidence I think it’s fair to say that the actual voting electorate was probably not entirely representative of the region.

Which leads us on to the representativeness of the flag’s imagery. Now, it is perhaps a truism to state that different images mean different things to different people. Although particularly pertinent to a large and diverse region like the Black Country, the assertion is equally applicable to any area, large or small. Some imagery will be highly meaningful to some people, and pretty meaningless to others, and indeed, some might actually have very negative connotations for certain groups.

One of the issues, therefore, of consulting a comparatively small number of people about heritage, identity, or a flag (or any other public issue, for that matter) is that some constituencies can potentially have disproportionate impact. For example, chainmaking was only particularly prevalent in some pockets of the historic Black Country, particularly Cradley and its surrounds, while glassmaking, the other industry shown on the flag, was centred in Wordsley and Stourbridge, which some die-hards might even claim were not part of the “real” or “heartland” of the Black country anyway. So the main motifs of the flag are not necessarily directly pertinent to the vast majority of the region.

The chain motif central to the controversy, meanwhile, is equally open to diverse interpretation. Many trade union banners over the last two or more centuries have prominently featured chains as a symbol of solidarity, while the motif appears prominently in the memorial to the female chainmakers of Cradley who, led by Mary McArthur, won their trailblazing campaign for a minimum wage. Indeed, of the six shortlisted entries in the 2012 flag selection competition, four of them included chains, so the issue of that imagery and the lack of discussion around its wider implications is in no way unique to this design.

Who gets to decide what a new local or regional flag looks like?

At times it can seem like a small coterie of those already interested in local heritage, perhaps one or a small number of institutions, like a museum or council, who naturally do what they can to interest others in the process but are constrained by the limitations of their networks and the usual barriers they face to consultation and engagement. If a decision is ratified by a local authority, that may make a flag “official” but it doesn’t necessarily mean that that flag is any more meaningful to ordinary people or that most citizens have had any more genuine input into its selection than any other civic logo, crest, or branding.

This is the case because the way in which “community engagement” often works is linked heavily to the short-term nature of public, lottery, or academic funding for programmes that often are ancillary to the main activities of museums, galleries, universities, and other large institutions. While there are amazing and inspiring community heritage projects and examples of local best practice and network-building across the country, in general there are a huge range of barriers to access, from class and financial situation to location and accessibility, from levels and experiences of education and digital exclusion to lack of English language skills, not to mention historic experiences of exclusion or invisibility within heritage or educational institutions from those of diverse ethnic or racial backgrounds.

Running a flag-creating competition in any setting where these barriers are prevalent is always going to make aspirations to represent as wide a constituency as possible incredibly difficult. And the barriers faced in every village, neighbourhood, town, city, and region will be unique to that local setting. It requires long term vision and really, really hard work to invest in the networks and capacity of communities to, not only access heritage, but to truly participate in shaping their shared and individual ideas about it with confidence and visibility in a public forum.

Dropping into any area without a strong community participatory infrastructure for a short project around flag design and some “official” ratification reflects to some extent the similar short term “engagement-based” approach of many other public and institutional projects which, as we saw in the Black Country, potentially can increase barriers and division. In any case, the potential for simply reflecting and reinforcing existing barriers and feelings of alienation from cultural and public discourse should mean that any heritage-based project should be asking hard question about whether they can truly deliver a representative process and outcome.

As the success of the Black Country flag’s wide adoption shows, however, it may be that a flag design competition can offer an excellent opportunity to gather and build momentum around local capacity and networks. In that case, again, proper legacy planning is essential to ensure that the work of the wider historical and heritage sector can retain investment and ensure deep and meaningful participation and representation going forwards. Again, we might ask questions such as:

Can regular, annual, or seasonal updates to flags be a way to constantly find new groups, communities, and creative ideas for engagement and investment in local capacity?

Is a flag, once ratified, the flag forever? What would be the process to change it? Should a time-limited review and renewal process be built into any ratification?

To what extent does an assumption of permanency actually build in future problems around meaning, engagement, and representation?

Whose Heritage?

Reflecting on the ad hoc process in the Black Country and how narrow the opinions and voices represented were brings to mind Stuart Hall’s seminal 1999 essay “Whose Heritage?” He outlines here his concept of “The Heritage” – capitalised – the assumptions about our heritage which are treated as given, timeless, true, and inevitable but which “it takes only the passage of time, the shift of circumstances, or the reversals of history to reveal those assumptions as time- and context- bound, historically specific, and thus open to contestation, re-negotiation, and revision.” Importantly, he makes the point that “those who cannot see themselves reflected in its mirror cannot properly ‘belong’”.

We have not yet had a region-wide discussion and conversation, in all localities and with people from all of the diverse groups that make up the Black Country, about what the area’s identity and heritage means to them. The competition essentially took place without widespread and ongoing community participation, within a small network of interested parties. If the networks and legacies of the great foundational work which took place across the region to mark the 2007 Bicentenary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade had had the capacity to be preserved and built upon, and a proper coming to terms with and open discourse about these difficult aspects of our shared past had been had before any idea of a competition were mooted, I’m certain that we would never have ended up in this position.

With blinkered thinking from the organising institution about whose voices and representation mattered, we ended up with a situation, exacerbated a hundredfold by the press reaction, where it would appear to many that: this group of people get to decide what the history and identity of the region are – if you’re not part of that group, and if you disagree with what they think, you don’t actually have a say. Worse than that, you’ll be called “barmy” and “ridiculous” and have your right to assert your voice undermined.

A feeling of belonging in the place you call home or feel connected to is an essential part of being a full, secure, and active participant in cultural and civic life. As vexillologists across the world know very well, flags can be powerful conduits for identity and meaning. Making decisions that can hugely and unpredictably mould these deeply powerful forces imparts a huge responsibility on the institutions and individuals who would assert a claim to designing a new flag for any location. Alongside the wider historical and heritage community, community flag champions can hopefully draw some important lessons from our experience in the Black Country and avoid making similar mistakes and inflicting unneeded upset and dislocation in future.

*This is an edited version of the paper delivered on 20 November 2021 by Matthew Stallard at the Winter Conference/AGM of The Flag Institute at the People’s History Museum in Manchester.