The Whole World a Black Country

Colonisation, Environment and the Idea of “the Black Country”

First published in The Blackcountryman, Volume 56, Issue 1 – Autumn, 2022

Previously in these pages I have outlined the centrality of preoccupations around the environmental despoliation of our region in the creation of the idea of “the Black Country” by bourgeois Victorian observers. In my work to catalogue every published reference to our region’s name in the nineteenth century I have lost count of the number of examples of British commentators for whom ours was the “shock landscape” of industrialisation which became a benchmark to compare other regions across the UK and the world against.

Despite poring over this plethora of accounts, I have struggled to fully comprehend the awe and terror that observers felt when they gazed on the fiery night and blackened sky, ground, and people. As the apocalyptic visions of wildfire infernos from locations across the world have fired into the collective consciousness in recent years and months, however, perhaps we can begin to understand the anxiety and shock that our region came to embody in the public imaginary.

The spread of the extractive fossil complex was described exactly and repeatedly by Victorian observers as the creation of new Black Countries across the globe and, in a sense, this vision has been played out – as terrifying new hellscapes created by the carbon-driven climate emergency develop on a planetary scale, one could even think of it as the whole world become a Black Country.

The spread of fossil capitalism was inseparable in their minds, and in reality, from the processes of colonisation. Further than that, however, politicians and commentators used imperialistic ideology to characterise a concept that caused such distress when observed at home as a progressive, indeed imperative, national and racial project when transplanted to colonised parts of the world.

The Extractive Fossil Capitalist Complex

To understand how this deep association was forged, it perhaps worth beginning by defining what the “extractive fossil capitalist complex” they understood was constituted of. I would characterise it as having two, thoroughly inseparable, components:

1) the scientific and technological knowledges, practices, and expertise that wrought ever more intensive and complicated feats of ingenuity and production

2) the economic and social relationships between land, people, and capital that could allow the successful application of those technologies and techniques

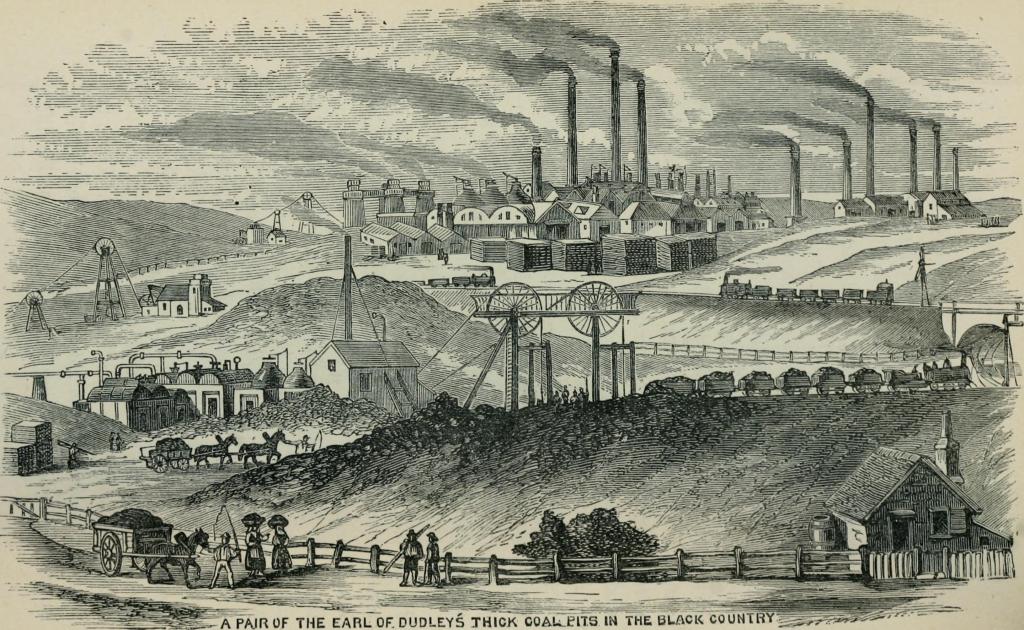

In world-historic terms the Black Country has a rightful and still-underappreciated place as foundational when it comes to the engineering and scientific breakthroughs and forms of knowledge that were later transported in the minds and bodies of people, as well as through published dissemination, throughout the world: Dud Dudley, Thomas Newcomen, Abraham Darby, John Wilkinson, and all of the others, named and unnamed. It wasn’t just engineering practitioners though. Other sciences, particularly geological surveying, were also fundamental to the successful exploitation and development of mineral resources and it is possible to speculate that thanks to the work of James Keir, the Black Country may have been the best-surveyed landscape in the world in the 1790s.

But just knowing how to turn those minerals into usable manufactures, and knowing where to find them is only half of the story. Deploying the vast resources and labour needed to put the landscape into extractive and industrial production required a suite of ideas developed over centuries that underpinned capitalisation:

< private property rights over land, enforceable by law and state-backed violence

< structures of investment and profit that allowed the pooling of capital that brought the necessarily large resources needed for successful exploitation

< receptive markets for the sale of extracted and manufactured goods

< a sufficiently large and reasonably-controlled or disciplined labour force

Indeed, much of the financial and legal apparatus around land, investment, and labour has roots traceable within projects of colonisation. The mineral-rich land of the Black Country, for example, ultimately derived its private property ownership (mainly by the Earls of Dudley) from the Norman Conquest. England’s pioneering joint-stock companies and investment programmes in the pre-industrial period, not to mention sources of crucial market demand, were colonising enterprises which laid the foundation for modern private companies. Enclosure and expropriation of tenanted and common land in the United Kingdom and Ireland, as well as various projects of enforced transportation, provided much of the workforce that created the booming wealth of Britain, at home and in its colonies, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

An understanding of the character of colonisation allows us to appreciate the extent to which the expropriation and exploitation of the mineral wealth and landscape of the Black Country was itself a process of colonisation, transforming the ground beneath their feet into a febrile new frontier for capitalism. In the Black Country and across the globe, therefore, science, technology, and expertise were understood as allied inseparably with expropriation of land, investment of capital, and deployment of labour in a complex that policymakers, investors, and colonists sought to pick up and take as a model to apply and remould again, again, and again.

New Black Countries Wherever You Look

Wherever they saw extractive fossil capitalism at work, it would seem, Victorian commentators projected their conception of our region onto other locations, to describe them as other “black countries”, or compare them to our archetypal landscape and complex.

In September 1893, the Times published an article on the “Black Country of Mashonaland” (in present-day Zimbabwe) reporting on missionary Isaac Shimmin’s account of visiting the Gambisa district where the “next village with its forges showed that we had also entered the iron or ‘black country’”, a summary of Shimmin’s published narrative where he described the settlement as “their Wolverhampton”. A Birmingham Daily Post article of May 1864 entitled, “A Dudley Man in Australia”, meanwhile, made clear how well-circulated knowledge of the colony was to its readers when it remarked that, “I need not tell you that Newcastle and district is the ‘black country’ of Australia”.

Of all of the published references in which British commentators projected the idea of the Black Country onto colonised parts of the world, South Asia featured most frequently. Two instances in 1870 include the Pall Mall Gazette of 15th March claiming that, “the Chanda coal field will serve as the black country of Western India for many years to come” and the Glasgow Herald of 30th June explaining that coal discovered between Midnapore and Chanda meant that, “in the very heart of India, we have an immense ‘black country’”.

The Times of 4th April 1877 compared no less than three areas of India to our region in one article. Readers learned that “the richest ores are, perhaps, confined to the Wardha Valley, Central Provinces – the ‘Indian Black Country,’ as some are even now venturing to call it”, while Warora was described as the “Indian ‘Black Country’ of the future”, and the long piece was rounded off by reports that an “abundance of the indispensable limestone is procurable in the Bengalee ‘Black Country’ likewise”.

Across three decades, repeated volumes of The Imperial Gazetteer of India, a key reference work for colonial administrators, detailed “the Raniganj coal-field . . . [where] in this ‘black country’ of India, which is dotted with tall chimney-stalks, many European companies are at work, besides many native firms”. The Birmingham Post of 31st July 1900 told readers, meanwhile, that, “It may not be generally known that the production of iron in Bengal, the Black Country of India, has become a thriving and remunerative industry”.

Comparisons to other parts of the world frequently used the Black Country as a benchmark for environmental devastation, such as the Times article of April 1876 describing a scene in Nepal of, “cleared spaces where fires have left a wilderness of stumps, leafless trees, and vast oceans of waving reed. It is a land wasted by fires . . . For many miles round each camp the columns of black smoke put you in mind of some busy district in the Black Country or Belgium”.

We hear from the Times report from Australia in August 1869 that “All about Balarat nothing is to be seen but tall chimneys and engine-houses and vast ‘spoil-heaps’ similar to, but, as the quartz is shining white, much better looking than, our black country”. It seemingly took until 1893 for a British visitor find a landscape more ravaged than our own – William Howard Russell reported in his 1893 Visit to Chile and the Nitrate Fields of Tarapacá that: “I have seen nothing in any part of the world so monotonous in colour and effect as this, the area of the greatest development of prosperous industry, of which so little is known in England. The Black Country . . . [is] gorgeously hued, bright and cheerful to the eye, compared to the Tamarugal Pampas”.

Bad Over Here, Great Over There

The cynical double standards of commentators, entrepreneurs, and policymakers when the idea of the Black Country was applied to colonised parts of the world are quite staggering for a modern reader. When applied to our region, the term almost always depicted its environment and its people negatively, yet, as soon as it was applied to British colonies it became an aspirational and positive appellation.

We find a hopeful tone in William Patterson’s Report on the trade and commerce of Montreal for 1865 that, “the complements in Canada of the British “black country” will, however, be those manufacturing regions which, it is believed, will grow up ere many years elapse”. The Glasgow Herald of 30th June 1870 was reprinting excerpts from the Calcutta Englishman outlining the “new sources of strength and new guarantees of the stability of British rule” that would come from the development of “an immense ‘black country,’” linked by coal-powered British-run railways and administered from, “places like Khandulla . . . [where] Europeans cannot only live, but flourish in a healthy mountain climate, and . . . [the] Chanda coal could be put down at a rate which would beat English mineral fuel out of the field”.

Key to these optimistic predictions of the spread of the extractive fossil complex was the work of hordes of geological surveyors, the inheritors and developers of the techniques of James Keir and his peers. Thus, the Pall Mall Gazette of March 1870 (mentioned above) stated that, “Unless Dr. Oldham, the superintendent of the Geological Survey of India, is over sanguine . . . the Chanda coal field will serve as the black country of Western India for many years to come”. Numerous editions of W. W. Hunter’s Imperial Gazetteer of India, an authoritative work built upon extensive surveying evidence, assert that Raniganj was the “Black Country of India”. A Times article in April 1877, meanwhile, updated on “recent analysis” of the extent of coal and other mineral seams across India, as well as chemical composition, quality, and potential uses, explaining that “the capabilities of the Indian ‘Black Country’ are a permanent factor even in the official anticipations of the country’s future . . . and the new forms which English enterprise may most advantageously assume in the East”.

Solving the Problem of the Black Country

What mental gymnastics could Victorian commentators be performing if they could possibly see the spread of the extractive fossil capitalist complex into colonised areas as a positive and civilising process whilst simultaneously projecting precisely the opposite characterisation onto our region?

A wide range of sources explain this phenomenon for us by demonstrating how the idea of the Black Country was constructed with all of the pervading imperialist, racial, classist, and eugenicist ideologies of the time forged deeply within it. In this twisted logic, implanting the fossil capitalist complex into colonised lands was not only positive because it extended British control and profits, it also offered a solution to the twin problems of the Black Country that most preoccupied bourgeois observers: the social and environmental impacts of industrialisation.

The same Times article of 1869 which compared the quartz mines of Balarat favourably with the Black Country was entitled “Virgin Territory” and made a lengthy case for ever-greater focus on colonisation, proclaiming grandly that the “Anglo-Saxon race has secured for itself all the unoccupied countries which are suited to its habitation, and has now to utilize them, to replenish them from its source, to flow over them like a living Nile, to scatter them with a seed of many cities and much people”. Of course, these regions were far from “unoccupied” but imperialist ideologues wove industrialisation and emigration into the narrative that could justify expropriation that “utilised” the land in a way they characterised as “productive” – namely the complex of private property rights, capital investment, access to markets, and a controlled labour force.

Constructing an idea that these lands were “empty” allowed colonisation to offer an answer to another major preoccupation that the idea of the Black Country posed to bourgeois observers: the social problems created by industrialisation, poverty wages, and poor infrastructure and sanitation. The article goes on to explain that “the emigration question is, year by year, becoming of imperious and paramount importance. Every Registrar-General’s return tells us of an increase in our population, and all through society, from the beggar that is turned away from the door of the workhouse because it is full to the gentleman who educates his sons and can find nothing for them to do, the stress of the struggle for breathing-room and foothold extends and is felt”.

Eugenicist ideas about the lower classes and population were extensively deployed to justify and popularise the colonising and imperialist projects of the era, thus we find the magazine of the Malthusian League in March 1883 including an article on “Low Wages in the Black Country” alongside pieces on “The Working-man in New Zealand”, “The Madras Malthusian League”, and “The Gospel of Malthus”.

Colonisation as Conservation

Colonisation and the creation of new Black Countries in expropriated parts of the globe not only offered a solution to the problematic classes and masses created by industrialisation but also to the distressing concerns about the “shock landscape” of extractive fossil capitalism and the environmental impacts on the rest of England if domestic industrial development continued apace.

The Times of 25th January 1878 detailed at length a speech by MP Henry Brassey which outlined the creation of industries in colonised parts of the world as a way to secure continued British wealth and prosperity without exacerbating the catastrophic environmental consequences at home. He asked the audience if, “it be a thing to be desired that our island should become the universal workshop of mankind? Would it add to the felicity of its inhabitants that the population of this huge metropolis should be doubled in number? Would they wish to see all Lancashire and Yorkshire honeycombed with coalpits, every hill crowned with a monster manufactory, and the Black Country of Wolverhampton enlarged to twice its present limits?”

Industrial development and the wealth and power it had imparted on Britain’s political and mercantile classes had, “inevitably involved the destruction of much that was fair and lovely in nature . . . A life without trees, and flower, and blossoms, which no breeze from the hills or the sea ever refreshed, was a life imperfect and wanting in the purest and best pleasures which it was given to man to enjoy”.

The solution to the environmental problem was to implant industrial development and remove the overcrowded population of Britain to “the Antipodes or the New World, under the Union Jack, or it might be beneath the Stars and Stripes of the American Union, [where] he saw before him a glorious vision of the growth of the Anglo-Saxon race”. For Brassey, this vision provided “a surer basis for their greatness as a nation than in the concentration of a redundant population within the narrow limits of their ancestral island home”.

Perhaps the apogee of this rhetoric came in the 1890s, at the height of imperialist bravado, exampled by a Times article of January 1895 which heaped praise upon Cecil Rhodes and Leander Jameson for carving out in southern Africa a “new territory . . . ‘nearly as large as Europe,’ . . . reputed to enjoy a climate where white men can not only live, but where white men can make their homes, and bring up their children”.

The potential for expropriation and pulling into the extractive fossil capitalist complex vast mineral resources lent itself perfectly to Jameson’s characterisation of the region as “a happy combination of Canaan, Ophir, and the Black Country”. Thus, an idea whose invention and development when projected onto our region managed to roll together layer upon layer of condescension and negativity when it was “over here”, uncomfortably close to home and visible to the brokers and beneficiaries of British wealth and pre-eminence, could be transformed into the biblical Promised Land itself when it was “over there” and out of mind, in someone else’s country, where its benefits could continue to flow into British coffers without having to viscerally confront the negative aspects of a system which threw people, land, and nature into the furnace in an ever-greater drive for production and wealth.

While they had little understanding of how increasing fossil fuel consumption created planetary-level impacts, the Victorian politicians, entrepreneurs and commentators certainly were acutely aware of the pollution and despoliation of nature that the rapidly developing and intensifying extractive fossil capitalist complex was generating, impacts which were expressed as deep negative preoccupations wrapped into the idea of “the Black Country”, which they projected onto our region.

Those powerful preoccupations when yoked to imperialism, colonisation, classism, eugenics, and racism proved a heady mix whose legacies we are only now beginning to recognise, appreciate, and unpick. For our region, placing our proud and truly world-changing history at the centre of the most critical debates of our time has the potential to put us on the map in a positive, constructive way – where we dismantle those tangled, toxic legacies and write our own, twenty-first century narrative, and map out new futures for our, and the many other, Black Countries they imagined across the planet.